|

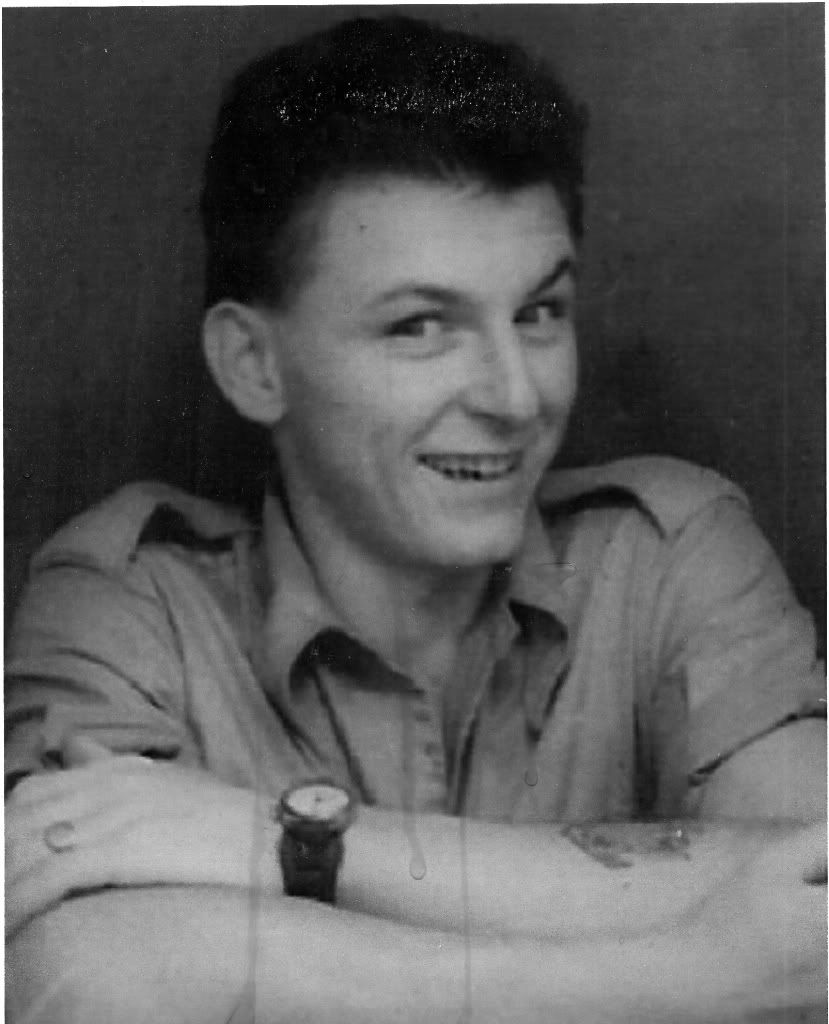

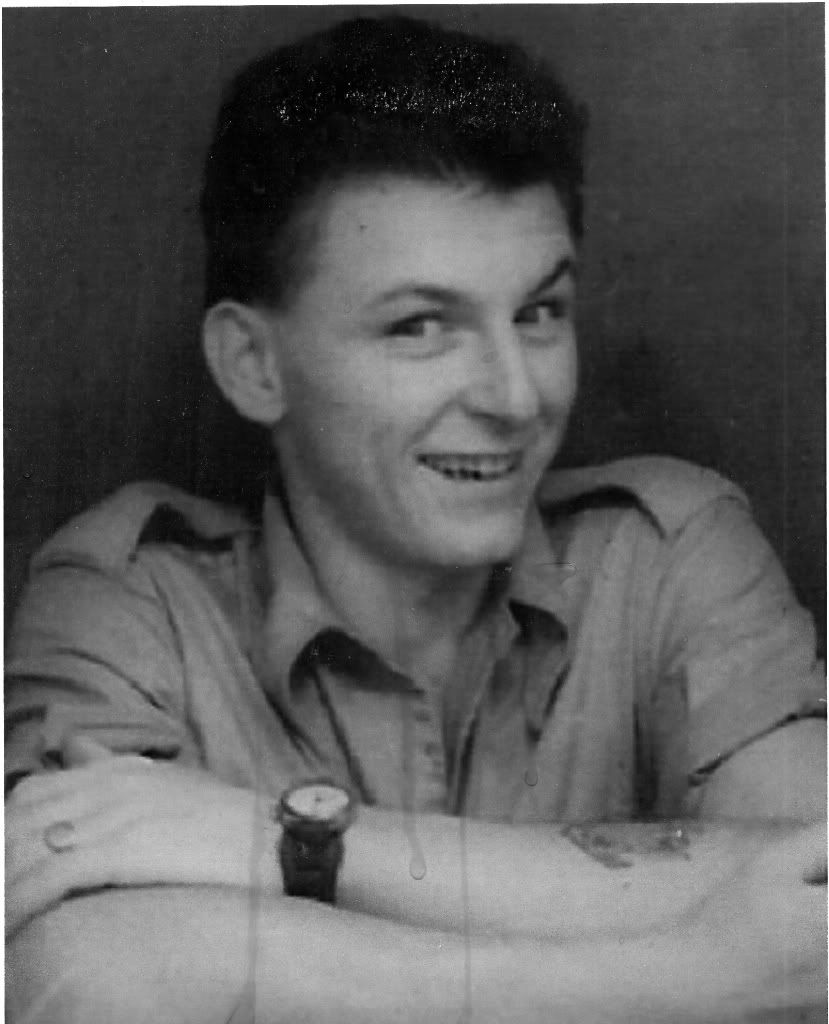

| The old man, with a still-fresh rose-and-anchor tattoo applied between whoring expeditions in wartime Lisbon, and probably about 19 years of age, or 1944. |

I've mentioned before that I didn't purchase a sailboat until I was 38, which is rather late to get in the game. This was despite the fact that I had a father who spent over a decade in the

British Merchant Navy, including 1941-45 when it was

a definitively hazardous occupation. Perhaps because, as a veteran of both the "

Murmansk run" and

post-war whaling in Antarctica, my father had been almost literally to the ends of the earth. He didn't show a lot of passion or interest in something as "civvy" as recreational sailing, any more than a retired demolitions expert would enjoy pulling apart drywall with a wrecking bar, I conclude.

|

| This odd and egregiously superannuated device is a "Steenbeck" film editing station. Compared to a razor block , my father thought it was a great leap forward, even if "tones on tail" contributed to his deafness. |

Being a mate on a circa-1950 merchant freighter and a "here, Dad, hold this" on a circa-2000 sloop actually don't have a lot in common. Throw in the fact that I was born 10 years or so after he "left the sea" for a new country and a

completely unrelated career as a

film editor, and the related fact that he was 75 when I bought my first boat, and about the only "seamanlike" behaviour I noticed the two of us sharing was a love of

Errol Flynn pirate movies and a tendency to notice when there were

nautical errors in movies like

Dead Calm or

Master and Commander. The rest of his side of the family were not involved with the sea, or so I believe. Someone at some point in the mid-1800s got on a ship from Ireland to Wales, but there it seems to end. Until me and Dad, I guess.

|

| This is the M/V Daleby, a modern (for circa 1950) example of a post-war general cargo freighter such as would have been familiar to my father. |

Nonetheless, I was quite aware from his unforced, salty expressions (imagine being a child in a Toronto suburb in the '60s told to "pipe down!" or to make one's toys "Bristol fashion"), and from the rapidity with which he could read a map and tie a knot, and from the occasional emergence of some picaresque and not often age-appropriate anecdote, that he had been the real deal: a working sailor.

|

| Unsurprisingly, it's pretty hard to source pictures of old-timey flensing action. Picture this with no protective gear except the wellies and you'll capture the blubber-splitting, gigantic-gut-spewing spirit of the thing. |

I recall pretty vividly childhood incidents in which tales were spun about under what unsavoury circumstances he got his tattoo, what aroma arose from whale guts after the three-foot long flensing pole had opened up the animal, and his avoidance of death several times at the hands of the Luftwaffe, the Kriegsmarine and assorted Japanese and Italian armed forces. At certain points, out would come a sperm whale tooth, along with the knife used to cut it away. Ripping yarns, indeed.

|

| For some reason, people carve these. |

It's no wonder he considered himself lucky, or that his life merited such a plethora of run-on sentences. He's pictured at the top of this post circa 1944, being at the time only about 19 and already having been bombed, strafed, tattooed and, if torpedoed, living to declare them misses or duds. His wartime friends were not so lucky, and after he moved here, he had little contact

with the few that had survived. He died in 2006 when my son was just past five, and it's a sadness to me that neither of my parents are around to be grandparents to him, nor to wave at us cheerfully from the dock when we leave.

|

| An essential tool for the wartime Merchant Navy mate: the pointy problem-solver. The one the old fella gave me looks a lot like this: Solingen steel. |

On the other hand, it's a rather sad fact that some people of my acquaintance have deferred their own cruising plans because of aged parents in need of assistance and management of their affairs. I would be at peace having that problem, actually, but it's a fact that moving to the front of the generational line chronologically and in a familial sense has its logistical upsides if you are wanting to cruise.

My wife's family is extremely Canadian, meaning they've been here since before Confederation (1867 for my non-Canadian readers) Probably there's Hudson's Bay Company employment and a little bit of native blood in the otherwise Scots-English mix. But my wife's father grew up close to waters of Lake Ontario and with plenty of access to little boats. Although he couldn't make a career out of it, he did draw(and saw built) a few of his designs. Unfortunately, all of his photos and drawings were lost in a fire many years ago, but he has seen that at least one of his designs, a 38 footer of sprightly lightness (he told me "10,000 pounds", which is indeed light for that LOA...Airex core may have been mentioned) is still sailing at around 30 years old.

| | | | |

| A Culross 38 built in the 1980s |

|

So, I guess one could say without fear of exaggeration, and despite, in my case, a rather delayed start, that the son my wife and I have produced is the son of sailors on both sides, and the grandson of sailors in a half-measure. As pedigrees go, that'll do. He's certainly fine with falling in the water.

|

| Lucas at seven in 2009 and about two pounds too light to easily right a turtled Optimist. |

|

| Got 'er done, however. I wish the old man could've seen this. |